Was saddened to learn of the recent passings of a couple humans who were both significant figures in my musical growings up … Bob Mascia and Ralph Bill. Sending love and condolences to their families and to all that loved them and will miss them.

They both influenced a ton of young musicians, having both served as band directors at Brownsville High School. I believe Bob may have actually followed Ralph in the role.

I was not one of their band students.

And I only really knew them for a fraction of my life, which was even a smaller fraction of theirs. But though I hadn’t seen either in decades, knowing them was — and will always remain — meaningful.

As does the fact that I’m writing this on an otherwise nameless summer Sunday afternoon.

__

I was 13 years old and standing in the kitchen after school one day while Mom was getting dinner ready.

When Dad came home from Sherwin Williams, walked in the kitchen and promptly informed me — outta nowhere — that he’d signed me up for drum lessons. And that he’d already met with the teacher, and made it clear that I was to learn all styles of music, “not just rock,” (I can still hear Dad’s voice emphasizing those words) … including waltzes, bossa novas, cha-chas, rhumbas, tangos, and of course, jazz and swing.

The specificity with which he relayed his expectations made it all feel like a foregone conclusion. But I was an agreeable kid, and drums were cool … so my reaction was along the lines of, “Ok.”

Bob was my drum teacher. He graduated high school with my older sister Missy (she reminded me that Bob played the lead in the high school musical their senior year – The Music Man — while she played piano).

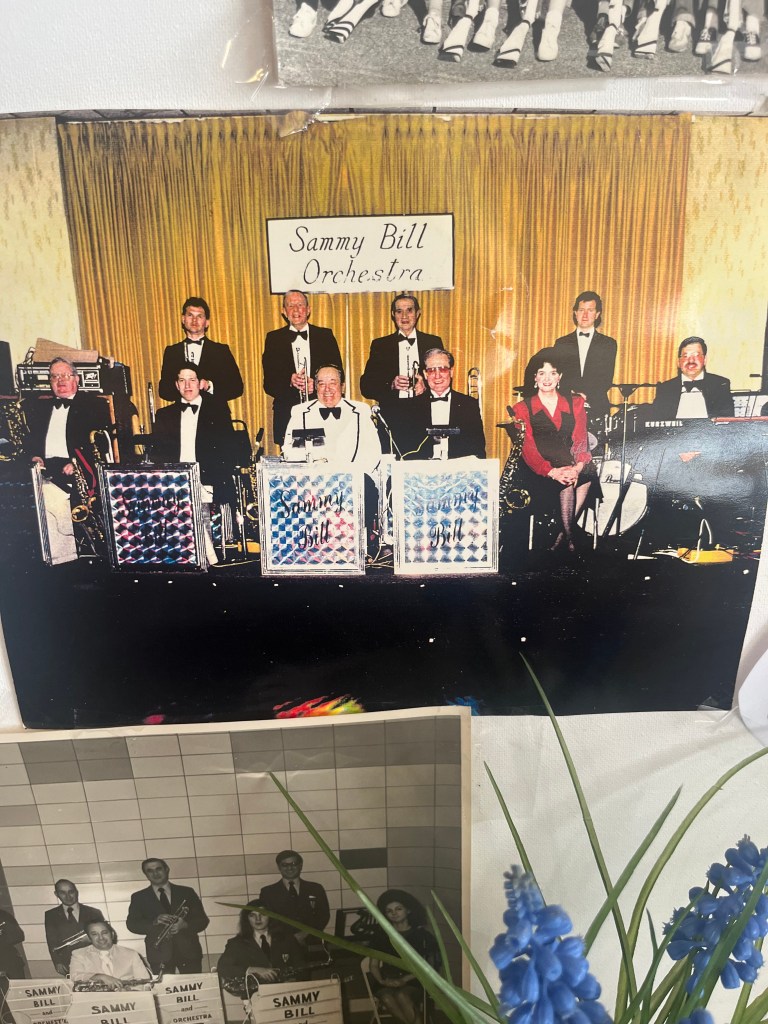

At the time of Dad’s kitchen conversation, Bob was playing steady in a local rock band and filling in with a few others, including the group my Dad played with — Sammy Bill’s Orchestra.

Gave drum lessons on the side downtown at Ellis’ Music Store.

First thing I learned?

Drums don’t start cool.

I got a pair of sticks and a rubber pad the size of a piece of Texas Toast.

Was informed that I had to learn snare drum before I’d be allowed anywhere near a set. For my parents, it was like a stay of execution.

Bob taught me how to read music, how to count quarter notes, eighths and sixteenths, what triplets were, how to bounce my sticks for open rolls. Graduated me to Charles Wilcoxin’s rudiments … paradiddles, drags and ruffs, and rolls of every dynamic, shape and size: fives, sevens, nines, seventeens, with an odd eleven and thirteen thrown in for good measure(s).

I was always somewhere between good and bad, never quite religious in my practicing.

But I stuck with it.

And a couple years into lessons, Dad surprised with the best Christmas present I’d ever receive — a set of Pearl drums from Ellis’.

I began alternating my weekly lessons with Bob between set and snare.

I remember my very first lesson on set, Bob teaching me the building blocks of how to assemble a couple basic beats.

Eighth notes on the hi-hat with my left hand (I’m a lefty), backbeat on two and four with my right on the snare, opening the high hat with my right foot on the ‘and’ of one and closing it on ‘two.’ Gave me two variations for the bass drum — four on the floor, and an alternate where the kick drum hit on “one” and “three-and.”

I still remember the exhilaration of the first time getting all four limbs to hold a groove.

It was a teenager’s equivalent of pedaling a bike under your own power for the first time. The inexpressible freedom that comes from being responsible for your own locomotion in the world. I can tell you the feeling’s the same whether the locomotion is physical or sonic. The Big Bang it was to me.

At last, drums were cool.

Occasionally I’d arrive a few minutes early for my Saturday morning lesson, climb to the top of the steps and find Bob just messing around on the kit.

Oh, was he a monster.

Every time I heard him play, from the first time to whenever the last may have been, I was in awe.

Got to hear him play once with Sam’s band. Though he held back for the kind of dance music they performed, he still couldn’t help overflowing the banks with his prowess.

It’s hard to keep a Ferrari tame.

__

Fast forward to the summer after ninth grade.

I was in the kitchen on an otherwise nameless Sunday afternoon, Mom fixing an early dinner since Dad had a gig that night. They played every third Sunday at the Moose in Perryopolis, three easy hours for an always appreciative crowd. Dad always loved that gig.

It had rained all afternoon, torrential summer thunderstorms … the kind that percussively pummeled and waterfalled rain on the aluminum awning on our tiny front porch.

The phone rang and I remember walking from the kitchen to answer it. It was Sam, calling to let my Dad know that the Moose had lost power from the storms and that the gig was cancelled.

I remember Dad being bummed, but also relieved to get his Sunday night back so he could prep for work the next day.

About 45 minutes later, we were eating dinner at the table when the phone rang again. It was Sam calling back to say that the power had come back on at the Moose … so the gig was on.

So Dad resumed his gig-prep ritual, getting a shower, doing his teeth (which took a good 30-45 minutes. I’m not sure there was ever a trumpet player more meticulous about his teeth), laying out his suit, his mute bag, etc.

No big deal.

Until the phone rang for a third time. Sam again. He’d gotten a hold of everyone except Bob. In the age before cel phones, when answering machines were still a novelty, you either got a hold of someone or you didn’t. Sam figured that Bob must’ve gone out to eat or something after learning that the gig was off.

“Tell Pete to get ready, just in case Bob doesn’t call me back,” Sam told my Dad.

Upon which I promptly started freaking out.

I’d tagged along on a couple of my Dad’s gigs, had listened to a couple cassette tapes of the band he’d given me, so I wasn’t completely unfamiliar with the music. But my drums had never left my practice room. I didn’t even have cases for them. I remember taking them apart that afternoon for the first time, afraid I wouldn’t remember how they went back together. When I wasn’t freaking out, I was praying that Sam would call back saying he’d gotten a hold of Bob.

Alas, a fourth call never came.

The rain had long since stopped by the time Mac came to pick us up. I remember carrying my cymbal stands out one by one, gingerly laying them down in the back of his Chevy Suburban, covering them with blankets so they wouldn’t be tempted to roll.

When we were done loading the truck, Mac commented, “They look like dead bodies.”

Not the encouragement I was looking for.

When we got to the Moose, Dad helped me set things back up and bought me a Pepsi to calm my nerves. Sam loaned me an oversized tux jacket, and a gratuitously large, velvet, clip-on black bow tie that wore crooked.

I’ll never forget his only instruction to me, which he delivered with his signature calmness: “As long as you begin and end with the rest of the band, you’ll be fine.”

By the time everybody tuned up and gathered on the bandstand, I was in full panic. I gave my full attention to Sam’s every word and gesture, locking into the tempos as he counted off the tunes.

But once a tune shoved off from shore, one person became my life preserver — Ralph, Sam’s son, who played keyboard. I hyper-focused on Ralph’s left hand, which he used to play the bass lines. Ralph’s left hand told me everything I needed to know about each tune … whether it was a foxtrot, a jump tune, a bossa nova, cha-cha … on down the line.

I remember little else about that evening other than surviving the longest three hours of my life … thanks to a constant stream of advice and encouragement from Alice (our singer) and the guys in the band.

When it was over, I gratefully collected their smiles and handshakes, and then collected myself before turning my full attention to trying to remember how to tear my drums back down.

Then Sam came over to me. Asked me to put out my hand.

Into which he put $25 … my share of the evening’s take.

I still can vividly recall my 15-year-old self’s feeling of surprise and exhilaration as I stared at the money in my hand. It felt like a million bucks to me.

In that humble transaction, I went from being a scared-shi*tless 15-year-old to being a professional musician.

I remember Bob making a point of that during my next lesson.

“No, I’m not,” I tried to quickly dismiss.

“You were paid for your services … that makes you a professional,” Bob informed me, setting the record straight.

Sam paying me was only the second most significant thing he did that night, though.

He asked if I’d be his regular drummer.

He said he was looking for someone who could make all the gigs. Bob sometimes played with other groups, forcing Sam to find subs. He wanted someone steady.

I can tell you with 100% certainty that there was nothing in my performance that evening that earned me the invitation. And I never grew to be more than one-tenth the drummer Bob was.

But I never gave Sam a chance to reconsider his offer.

And, you know what? Bob never said a single word about my displacing him.

So, for the next 13 years, I got to share a bandstand with my Dad.

And with Ralph, too.

__

When I think of Ralph, I think of how much fun he had while playing music. When his hands weren’t on the keys, he kept the band in stitches telling jokes. From the moment we’d arrive at a hall through set-up. Between sets. While we were tearing down and loading up. How he loved making people laugh.

And, oh how he loved good food, too. The more unpretentious the surroundings, the better, as far as he was concerned. I can still hear Ralph saying, “You can’t eat atmosphere,” a line that I still quote to this day whenever I find myself enjoying delicious food in less than fancy surroundings. I credit Ralph every time I quote him.

__

As I was driving Route 40 towards Brownsville a couple Wednesday’s ago to pay respects at Ralph’s visitation, I found myself thinking of all the New Year’s Eve gigs we played together. After playing Auld Lang Syne at midnight, the band would stand up and we’d shake hands. I always set my drums up next to Ralph’s keyboard, so Ralph’s was usually the first hand I’d shake in the new year. I can say as I write this I now consider that an honor.

When I got to the funeral home, I spent a few minutes looking at the old photos they had placed around the room, mostly of Ralph’s life in music and love of family. There were a couple pictures of Sam’s old bands, one from the very early days, and a later one from when we played together. Sam in the front row in his white tux, Ralph smiling from behind the keyboard. Dad in the middle of the trumpet section, and me in crooked bow tie and glorious mullet.

“So many of them are gone, now,” Ralph’s wife Hillary said of the photo, when I offered my condolences. “Sam, now Ralph, your Dad … Roger … Diz.”

It’d been about 25 years since we’d last seen each other. Hillary used to come on some of the gigs. I invited Karry on a couple New Year’s Eves and they’d keep each other company.

“I remember the first time you played,” Hillary recalled. “You wrapped your drums in blankets.”

I told her that Ralph’s left hand was pretty much responsible for getting me through that first gig. And how much I treasured those times.

On my way out, I signed the registry, taking note of the names of some of the guys I was fortunate enough to play with all those years ago.

I didn’t stay long.

Just long enough to be reminded of days of Auld Lang Syne, and what good days those were.

Learning of Bob’s passing barely a week later … I was reminded that none of those days would have even been possible without Bob’s presence in my life … and his absence one rainy Sunday afternoon.

There’s no such thing as a nameless Sunday.